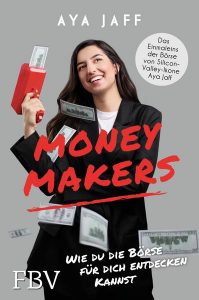

‘Mrs Code’ is the nickname in Germany of 24-year-old Aya Jaff, who was only 15 when she built her first software programme on the school curriculum at high school, which very quickly brought her fame, especially after a brief three-line story of her engagement with technology at a very young age was published in the New York Times when she was 17. She was under 21 when she became the most well-known woman software developer in Germany. She worked for several technology companies as a consultant and was only 22 when she set up her own company to work on combining innovative fashion projects with technology. She is a true innovator and young spirit, as the magazine Forbes listed her in their 30under30 young entrepreneurs list in 2019. She is a strong advocate for the platform ‘Girls in STEM’, which aims to inspire high school and college students to be interested in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, and she mentors young coders at countless events. The passion for combining finance with technology, aiming to explain the stock market in an understandable way to people who have no idea about finance, resulted in a book, Moneymakers, in 2020, which became a SPIEGEL-Bestseller.

Aya was only 2 when her family migrated to Germany from the city of Sulaymaniyah in Iraqi Kurdistan. Being located to a migrant neighbourhood by the German authorities when they first arrived provided her with a cherished and enriching environment; I could see that remembering her playful childhood days with her friends made her joyful. It is true when on earth would she have had the chance of hanging with a Sri Lankan in the backyard of her home in Sulaymaniyah? However, it is also true that constructing ghettos is the cheapest and laziest way of dealing with migration in Europe.

Subversive identity through pinkification: not a spectacular contradiction

No one can deny that through her public talks and events Aya wants to show that technology is not a purely male domain and that this applies not just in Europe. What she told me when I met her shows that you cannot simply be just a woman who is into technology but needs a feminist consciousness as well, including with regard to the colour of outfits you choose. Although style and colour consultant Angela Weyers says “it is not advisable for women to wear it to work in the corporate world, as they are less likely to be taken seriously”, Aya exclusively wears pink suits, not to tick the ‘stereotypical girliness’ box of the gendered consumer-centric world but instead to deliberately make herself a target in order to engage with these sexist attitudes towards women in the technology arena, a way of saying “before you match me with the colour pink, I will do it myself”. Of course, with this ‘pink act’, she also tries to redefine the colour pink, which has been seen as a “testament towards the patriarchal hierarchies”,[1] to a “subversive and grown-up”, which means it “no longer means warm and fuzzy”. She wants to say that entering technical domains does not necessarily mean sacrificing major aspects of her feminine identity. She is also aware of the extra work she must do to prove that she can be both a pretty woman and smart enough to understand technology, not just to justify herself to men but also to her counterparts.

Although the enduring identification of technology with manliness is not inherent in biological sex difference, different childhood exposure to technology, the prevalence of different role models, different forms of education, and the extreme gender segregation of the job market all lead to what Cockburn describes as “the construction of men as strong, manually able and technologically endowed, and women as physically and technically incompetent”.[2] While occupations encourage gender stereotypes so does technology. While kitchen or household appliances are feminized and are invariably identified with women’s labour, computers and other complicated technologies such as factory machinery, military weapons and work tools are reserved for the masculine sphere.[3]

As a matter of fact, the cultural stereotype of women as being technically incompetent or invisible in technical spheres started in the West, and the fierce fight against it is also rising up in the West. The spotlight on Aya’s German and European platforms is one aspect of this fight against the exclusion of women from ‘geek culture’, and a step towards remedying the gender deficit in both industrial and digital technology

Despite the fact that it sounds flattering, Aya is not happy with the title ‘Mrs Code’ which the German media has applied to her. She explains, “sometimes when the press portrays me as this ‘female coder’, I really get anxious. I do not want to be that coder that stands for the whole generation of women in technology. It is not right, because there are a lot of women who do much more than me or do completely different stuff than me. I do not feel comfortable with that title. I always told the press, please stop calling me Mrs Code”. I asked whether the media applies similar appellations to men. She responded “You mean Mr Code? They never do. For example, there is a guy who is 37 and built a university called ‘CODE University’. He is not a coder himself. He does not play a coding role in this. It is legitimate that he has established that university even if he is not a coder. He does also not have to justify this with a diploma because he is a man”.

The existence of power segregation between women and men (in favour of men) in technological discourse undermines women’s technical skills and domains of expertise. Comparing herself with the German guy being called ‘coder’ without even coding just because he is a man, she says “I cannot imagine me doing what this guy did without expertise because it blows my mind, I always get backlash and comments like ‘is this girl coding? Has she done enough? I think I have done more than her’. They always find a way to take away that thing that makes me the special one in the articles. I always reply ‘Have you ever coded the biggest social finance game in Germany? No, you haven’t. Have you broken in the security issues with a software company? You haven’t. Have you done this? Have you done that?’ I am trying to tell them that I have put in the work. You cannot just say she is special because she is a girl”.

Positive racism: the problems of perfection

Regardless of how much I appreciated her achievements, I could still not stop wondering what makes her special amongst other German young women tech and digital entrepreneurs in the eyes of German media and platforms. When I asked her this, she said, “there are many young women who could code”, but the difference lies in the fact that she likes public speaking. I was still not very convinced. When I asked if was a German, she abruptly responded “what do you mean? I am German. I am a German citizen. You meant if I was born as a German or had a German look?”. As she is accustomed to everyone scrutinizing her successful media profile with doubt and suspicion, my searching questions as I tried to understand the real agenda behind her fame in the public discourse must have made her think of me as ‘one of them’.

Aya Jaff

Although digital spaces and mainstream media still present an overtly hostile portrayal of migrants and minorities, apparently Aya is not one of them, as she challenges the hegemonic migration discourse. An idea that is closely linked to the four characteristics of a hegemonic migration discourse is that migrants are seen only as passive objects and merely victims of external circumstances (wars, disasters, economic hardships) or mafia-like networks run by unscrupulous ‘human traffickers’ or ‘refugee smugglers’. What is being overlooked is that migrants can also be agents and subjects capable of acting, like Aya. However, one may object to the idea that Aya is a ‘perfect example’ of how migrant youth should be or should appear, with her spectacular looks and outstanding prospects. Aya finally understood my insistence on understanding why she was in the spotlight in Germany. In relation to the highlight on her home country as Iraq in media coverage about her, she added, “putting me on the stage means that ‘hey this woman is the perfect example of why we should not think women are dumb or people from Iraq can’t do stuff or they are lazy. Look at her. She is perfect and everyone should be like her. That is discrimination, not everybody should be like me. There are so many other qualities that people can bring to the table”.

In fact, Aya’s portrayal as secular, liberated and having control over her life, as the ‘dream Middle Eastern migrant image’, makes other migrants look like failures. To them, Aya is the rare healthy apple amongst the rotten ones in the basket. But despite all, Aya is the last person to be blamed for that.

[1] Signe Pierce. https://alicebucknell.com/articles/a-brief-history-of-pink

[2] Cynthia Cockburn. 1983. Brothers: Male Dominance and Technological Change, London, Pluto Press, p. 203.

[3] Judy Wajcman. 2009. “Feminist Theories of Technology.” Cambridge Journal of Economics, p. 14.

Özlem Belçim Galip is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Oxford. She is the author of Imagining Kurdistan: Identity, Culture and Society (I.B, Tauris, 2015) and Civil Society versus State: New Social Movement and Armenian Question in Turkey (Palgrave, 2020). She is currently at the postproduction stage of her ethnographic documentary film “Anywhere on this Road: Letters to My Unborn Daughter” on Kurdish intellectual women in Europe and her own personal journey as a Kurdish woman migrant, shot in various cities in Turkish Kurdistan along with Germany, England, and Sweden.